The Modern Era in the United States is typically defined as the period from 1930 through the 1970s. Buildings from this period often feature clean lines, open floor plans, and large windows and are distinguished by their embrace of the technology of the era. Materials such as steel, glass, and reinforced concrete were frequently used. As these buildings age, and as performance expectations of occupants change, modernist building owners and stewards can face complicated decisions regarding repair, renovation, and/or replacement of the historic facade elements.

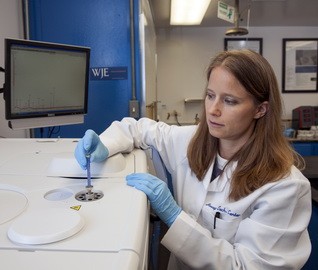

In this complimentary, one-hour webinar, engineers Martina Driscoll and Mark Schmidt, architect Bryan Rouse, and historic preservationist Becky Wong examine the glass elements of modernist buildings and, through project case studies, discuss the tradeoffs between increased performance (including aesthetics and durability) and historic preservation.

By the end of the webinar, you will be able to:

- Identify character-defining features of glazing used in modernist structures

- Understand the history of architectural glass

- Describe the current industry definitions of "safety glass"

- Explain trade-offs between historic glass retention/conservation versus replacement

more to learn

View this webinar in our interactive audience console to earn 1 AIA learning unit, access related resources, submit questions to the presenters, and download a certificate of completion.

Bryan K. Rouse, Associate Principal

Mark K. Schmidt, Principal

Rebecca D. Wong, Senior Associate

LIZ PIMPER

Hello everyone and welcome to today's WJE Webinar, Conservation of Glass in Modernist Architecture. My name is Liz Pimper and I'll be your moderator. During the next hour, engineers Martina Driscoll and Mark Schmidt, Architect Bryan Rouse and historic preservationist Becky Wong will examine the glass elements of modernist buildings and through project case studies we'll discuss the trade-offs between increased performance and historic preservation. This presentation is copyrighted by Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, and now I will turn it over to Becky to get us started. Becky?

BECKY WONG

Great. Thanks so much, Liz. Thanks for being here with us today as we spend time talking about glass and modernist architecture. We'll first go over a definition of modernist architecture. We'll describe how glass is used in those architectural styles, annealed glass fabrication methods followed by conditions that may lead to repair or replacement of the glass or glazing frames. We'll also discuss contemporary fabrication methods of glass, technological advancement and current code requirements that may affect any glass project you have. This would also include fabrication limitations for special glass with color.

At the end of the presentation, we'll wrap up with two case studies that took differing approaches to the glass. Both projects are historic, but one included full replacement of the glass and the other retained all of the glass. The ultimate goal is to help you understand building conditions that could affect your glass and for you to become more informed when you face a window glass or glazed facade project. This is of particular importance for modernist structures as they continue to age, though much of this information is also germane to contemporary structures as well.

We'll also have time to receive questions from you with a lot of topics to discover. Let's dive in. So what is modernist architecture? The modernist architectural style spans from approximately 1920 to the 1970s, which has a wide variety of styles that fall under the modernist umbrella. The list I have here is not fully inclusive, and if you're interested in learning more, I'd highly recommend visiting the Docomomo website I have listed at the bottom.

I've also put date ranges here for each style, just for context, but they're not meant to be exact dates as regionality always plays a part in execution and presence of architectural styles and materials. The first style is Art Deco, which ranges from the 1920s and into the 1930s. Common features of this style are expressive and pattern ornamentation, often in geometric forms. There's an incredible variation of window sizes and patterns. A notable building of the style includes the Chrysler building in New York designed by William Van Alen.

We then see a transition to streamline or art modern, which minimalizes ornamentation but introduces curved or sweeping forms. Windows are more often seen in a horizontal ribbon pattern or even as oculus or round windows. A notable of this style includes the Coca-Cola factory in LA designed by Derrah. Now mid-century modern in itself is a grouping of architectural styles that includes brutalist and international style.

Brutalist style is focused on mass and bulk with a common building material being exposed concrete, and what you see on the outside is visible at the interior. No notable ornamentation is utilized. Windows are seen in punched or ribbon style. A notable building of the style includes the Robert C. Weaver Federal Building, also known as HUD, which was designed by Marcel Brewer.

International style is much of the same of no ornamentation and maximizing size, but you see more use of other building materials such as metal with smaller buildings also using wood. Windows are more often used in ribbon patterns or in larger format, so big sizes with a notable building of this style, including the UN headquarters in New York by Niemeyer, Le Corbusier, Harrison, and Abramovitz. I've also put a question mark at the end of the date range. This style still lives on and what we see today. The slide also shows some architects in the modernist movement, but again, not fully inclusive.

Glass is used to transmit natural light to interior spaces, but modernist architects also embraced glass for its ability to create a sense of transparency and openness, reflecting the movement's emphasis on functionalism and minimalism. Large glass windows and facades allowed natural light to penetrate deep into interior spaces dissolving the boundaries between indoor and outdoor environment. The two photos shown here are of that Martin Luther King Memorial Library by Mies van der Rohe.

Take notice of the visual difference of the glazing during the day compared to at night. During the day you see more bulk and mass with a visually monolithic black steel curtain wall with bronze glass floating over a recessed first floor with clear glass curtain wall. Their clear glass allows pedestrians to walk in, walk by and see no attempt for privacy to the interior spaces. At night, the building transforms and almost softens with the interior more visible through the upper floor glass.

We also see the use of glass set in a band of ribbon windows, both horizontally and vertically, unique shapes and large pieces of glass that extend from floor to ceiling to create an early form of a curtain wall. The photograph shown here for ribbon windows is the Gropius House in Lincoln, Massachusetts. The use of glass is part of the architectural style, so we see not only clear glass, but also tinted and colored glass.

At some point, glass in a building may need to be addressed. Glass doesn't exist in itself with architecture, it is part of an assembly. How the glass is captured and supported along with the material is important to understand when considering the impact on glass performance along with a potential deterioration or distress mechanisms of the glass. Distress or deterioration of the glass or glass frame and support can lead to glass loss water and/or air infiltration and other issues that impact the overall condition and performance of the building.

Historically, the glass was captured into wood frames. Typical deterioration to be considered are wood decay from water exposure, wood degradation from UV exposure and potentially insects. This can lead to loss of materials and if at support members loss of glass. The photo I have here shows a horizontal muntin and meeting rail sagging, which is also separated vertical muntin.

As the demand for larger and more durable window assemblies grew, materials like iron and steel began to be used. Cast iron and later wrought iron were employed for their strength and ability to support larger panes of glass. Steel frames with their strengths and flexibility became popular in the earliest 20th century, particularly in modernist architecture. Steel windows allowed for expansive glass panels and thinner frames aligning with the modernist principles of transparency and openness. This picture is the Glass House in New Cannon, Connecticut.

This is another type of steel window, which is more of an industrial application. With ferrous metals, the most often condition will be related to corrosion, which is shown here where it's forming on the muntins where coating and glazing putty is no longer intact. Corrosion is expansive and can result in metal to glass contact and pressure along with a loss of metal material.

In concrete facades, which can be cast in place, cast stone or precast, the glass plates may have thinner metal frames so it isn't as visible above the concrete or it could be simply set on sealants without a frame. The detail here is just an example of what a concrete facade and window could look like. Depending on the metal of the frame, there could be a potential for corrosion. If simply sealed weathering of the sealant could result in the potential for direct concrete to glass contact. Also with windows without drip edges at the top of the window, that actually can result an alkali rundown from the concrete onto the glass, which leads to staining and etching.

While we're focused on modernist architecture for this presentation, the information on glass is applicable to other architectural styles as well. Glass during this time period often consisted of plate glass, a type of flat glass known for its smooth surface and clarity. The classic method of making plate glass involved heating raw materials and spreading the molten glass onto a flat surface to slowly cool, which relieves the internal stresses. This process is known as annealing. The glass was then rolled and polished to remove imperfections, which is shown in this photograph.

By the 20th century, advancements and glass production such as the development of float glass by Sir Alastair Pilkington in the 1950s really revolutionized glass manufacturing. The float glass process, which involves drawing molten glass onto a bed of molten tin to achieve a perfectly flat surface, largely replaced earlier methods and is the predominant technique used today for producing high-quality flat glass.

For colored glass constituents or impurities in the mix is altered and uses metallic oxide or other substance in a colloidal state to impart the desired color while remaining transparency. I'll now turn it over to Martina who will dive into more detail on contemporary replacement glass performance and impact. Martina?

MARTINA DRISCOL

Thanks. Now that Becky's defined what modernist glass is, let's talk a little bit about the conserve versus replace decision-making process. I'll talk about some general performance characteristics for glass in the next few slides. We could do a whole presentation on glass performance, so apologies that this will be a bit truncated, but hopefully the trade-off implications of these characteristics is clear. We'll also discuss these in more detail in the context of our two case studies.

Becky talked about the fabrication of annealed glass. For contemporary fenestration, safety glazing is required by the international building code when all four of these conditions exist, and annealed glass alone doesn't meet those safety glazing requirements. It's also interesting to note that while code will often allow for replacing kind in restoration work, even if the work doesn't meet current code, it does require replacement with compliant glass in most situations, though there are exceptions including for decorative glazing.

So what is safety glass? It's basically a glass with characteristics that make it less likely to break or less likely to pose a threat if it does break. Common designs include monolithic tempered glass and/or laminated glass. Typical tempered glass goes through a heat treatment process where it is fed into a tempering oven on rollers. The oven heats the glass to a temperature of more than 600 degrees Celsius, and then it undergoes a rapid cooling procedure called quenching, which cools the outer surfaces of the glass much more quickly than the center.

As a center of glass cools, it tries to pull back from the outer surfaces and as a result, the center remains intention and the outer surfaces go into compression. It gives it a strength of about four times that of annealed glass. And another benefit of tempered glass that I think most of us know about is that when it does break, it should break into smaller pieces without sharp edges.

Laminated units are two or more pieces of glass that are stuck together or laminated together by an interlayer such as those listed here. If a piece of glass does break, the goal would be that it remains in the opening, thanks to that interlayer. Just to note here too that both of these concepts were understood at the time of the modern movement, but were not widely used. A quick mention here too, that you can produce something called heat-strengthening glass through a slower quenching process resulting in an increased strength, less than fully tempered, but more than annealed. But without the fully tempered glass breakage pattern that I talked about, it does not meet the safety glass requirements when used alone.

And finally, for those of us at a certain age, when we heard safety glass, we thought of this, traditional wire glass. It emerged in the late 19th century and incorporated a layer of metal wire mesh embedded within the glass when it was made. It was thought to be stronger, acting like reinforced concrete and was widely used for fire-rated applications in particular. And while resistant to fire, it was actually found to be weaker than a neoglass of the same thickness. It was also very dangerous when broken. So by the 2006 edition of the International Building Code, traditional wire glass was no longer considered a safety glass for any occupancy type.

So after safety, probably the improvement that we talk about the most it gets maybe the most press is the chance to increase thermal performance and decrease energy use. This is usually achieved by the introduction of an insulating glass unit or IGU comprised of glass, two panes of glass with air or multiple panes of glass with air or gas-filled spaces between them. The performance of that IGU can be further improved by the introduction of something called a low emissivity or a low-E coating onto the glass surface. They work very oversimplified, but they work by limiting certain wavelengths of light from passing through the glass.

This is a chart provided by Cardinal Glass that compares various of their low-E coatings to a clear glass air-filled insulating glass unit. U-value measures how well the window insulates. The lower the U factor, the better the window insulates. Solar heat gain coefficient measures how much of the sun's heat comes through that window. It can range in value from zero to one. The lower, the less solar heat the window lets in. Now that can be good or bad depending on your climate zone.

You can see that depending on the type of low-E coating, the addition of that coating can significantly affect the solar heat gain coefficient. The visible light transmission, it's the fraction of visible light that passes through the glass relative to the total visible light that hits the surface. A higher VLT percentage means more visible light is transmitted. You can note the trade-off here between visible light transmission and solar heat gain.

A glass selection can also reduce UV transmission and the associated risk for fading or damage to interior finishes. And finally, contemporary glass also offers the opportunity for increased acoustic performance. So great, right? Sounds good. Lots of benefits for contemporary glass. Well, what about the downsides? One obvious and significant negative would be the loss of the historic fabric, and we'll set that aside for now along with increased cost and talk briefly about other potential downsides of we'll call new glass.

While all glass can exhibit objectionable aesthetics like bowing or blemishes, there are issues that are unique to contemporary glass, one of them is shown here. As I mentioned, typically tempered glass is produced in a furnace where its moved over rollers. As that glass temperature increases, the glass becomes pliable and can sag slightly between the rollers resulting in a reduction in surface flatness known as roller wave as seen here. Admittedly, this is a bit of an extreme example. The ends of each piece of glass also tend to sag to an even greater degree, and this sag is known as edge kink.

This photo is an example of an isotropy, basically an iridescent strain pattern that occurs in heat-treated glass. Just to note here too, that forming glass into insulating glass units can amplify the appearance of some distortion. Another condition that's limited to fully tempered glass is nickel sulfide-induced spontaneous glass breakage. Nickel sulfide inclusions are microscopic contaminants in the raw glass that are introduced during the production process.

Heating the float glass can cause that nickel sulfide to change from its normal state to a smaller crystalline structure, and when the glass is then cooled quickly as part of that tempering process, the particle is unable to change back to its original form, and over time it can convert back to the larger structure inducing breakage. The picture on the right shows the distinctive figure eight breakage pattern indicative of this type of failure.

Insulating glass units can appear bowed or cupped due to net pressure differentials across the IGU caused by changes in temperature, atmosphere pressure or both. And the low-E coatings are technically noted to be clear or transparent, they do affect the view through the glass from the interior as well as the exterior appearance. The coatings with the least influence on appearance are called neutral low-E coatings, and perhaps maybe most obviously most interventions that improve energy efficiency or strength will affect the overall thickness of the glass.

So we've discussed some of the aesthetic impacts of replacement glass along spontaneous glass breakage, and I'll hand it off to Mark who will discuss some structural considerations of glass in particular thermal stress in more detail. Mark?

MARK SCHMIDT

Thank you, Martina. Some obvious questions that come to mind with regards to glass analysis are why, and so what? The why of the matter is, as Martina just explained, we're trying to ride a fence between maintaining the existing aesthetic, the historic fabric of the facade while improving performance, and that drives us to select the flattest glass that we can find. And commonly what that consists of is either monolithic or laminated annealed glass and they happen to be the flattest and also the weakest types of glass in their respective categories.

So what does kind of analysis does that drive us to perform? The first, as Martina discussed earlier, was more of a code review of safety glazing requirements. If safety glazing is required in a specific application or hazardous location, would drive us to selecting laminated annealed glass. Modern codes like the IBC require replacement glass to meet current standards for new glass.

So that means ostensibly that you would need to design for modern wind loads. If that's too onerous, perhaps you can get a variance, but in either case, analysis for wind loads is relatively easy using ASTM standards and available softwares. What's a more difficult characteristic to analyze of the weak annealed glass is its thermal load resistance. What do we mean by thermal load? How's that induced in the glass?

Well consider, for example, the sun coming up on the horizon from the east hits the glass, warms up the center and the edges in the historic glass are usually captured and remain cool. What this does is it's like an expanding balloon where the membrane wants to get stretched and there's some high tensile stresses that result at the glass edge to create the kind of failures you see in the lower right-hand photograph there relatively weak edges.

So how do we guard against it? What are kind of tools do we have available? Well, thankfully for monolithic and laminated annealed glass, there is an ASTM standard. It has limitations. You can't analyze every configuration that you might want to, but it also has a referenced paper within it that allows you to calculate the probability of breakage for certain configurations. And as Martina and Becky will show later, our experience suggests however, that those estimates of breakage are pretty conservative.

So what other tools are available other than ASTM? In Europe, they have some software that's been developed and we've experimented with it, tried to calibrate it to field data that we took on earlier projects and we just couldn't reconcile the results. So we developed two in-house procedures. One's a two-dimensional approach that uses ASHRAE data in LBNL windows program to estimate the center of glass temperatures.

Then those center of glass temperatures are fed into the LBNL therm program to determine the edge temperatures, and it's the difference between the center and the edge temperature that's used to calculate the resulting edge stresses or thermal stresses at the edge of the glass. So what if we have a more complicated configuration that we can't cover by either of those two methods? We developed a three-dimensional approach using the Maya HTT software, which has solar, infrared, convection and conduction capabilities.

And you can see on the model at the right, we can not only analyze replacement historic glass, but also analyze glass for new projects, glass that may utilize insulating glass units and shadow boxes and shadows created by sunshades shown there in the model to the right as well as pattern ceramic coatings. It does require some amount of engineering judgment to do this analysis. You need to select configurations out of the international glazing database that are similar to what you're trying to analyze.

And we do know that we need to further calibrate this and we're attempting to do that currently using some laboratory measurements. So with that, I'll turn it back to Martina and Becky who will describe a case history where they utilized the more common ASTM approach for a thermal stress analysis.

BECKY WONG

Great, thanks, Mark. So I'll go through two case studies, which what I previously mentioned had two different approaches on both sides of the spectrum for glass treatment. Our first one will be the MLK Jr. Memorial Library located in Washington D.C., which is a Mies van der Rohe structure. This showcases a project where sympathetic replacements were implemented. For context, the building is four stories tall and measures approximately 355 feet by 180 feet in plan.

In accordance with typical Miesian design, the exterior is focused on structure without undue elaboration or ornamentation. The rectilinear curtain wall is constructed of simple steel angles, beams, columns, channels, and plates coated with black paint. And to complete the framing of the enclosure, most of that interior flat surfaces have been filled with glazing. The upper three floors, which incorporate dark bronze glazing extend to the full dimension of the building plan.

The ground floor is set back forming a 30 foot deep loggia along the south facade with a loggia reduced to 10 feet at other facades. The clear glass also allows for unobstructed views into the expansive rooms of the ground four public space of the library. The District of Columbia Public Library set out for a complete restoration of the library. Our involvement was on the exterior restoration, which I have our abbreviated scope on the slide for reference. As part of that program, the deteriorated conditions that the steel and glass curtain wall needed to be addressed.

Over the years, the exterior glazing seal had aged and resulted in water entering the glazing pocket and corroding areas of the steel stops, some of which resulted in glass breakage. Along with human impact, this resulted in glass breakage over the years and as glass broke, DCPL would install new glass of the same thickness to finish the repair. This had resulted in a mix of original glass and heat treated units, which were visibly different, particularly in the bronze lights and especially when viewing reflections of adjacent buildings.

So going back to what Martina showed on a previous slide, the reflections of the adjacent building, which we know has straight walls that show a bow or a distorted image in the glass reflection are heat treated replacement units. So looking at this photo based on this, we believe that all of these windows were replaced at some point, so I'll remove those outlines so you can take a look at the reflections again.

During design, we were also able to work with the GC and glazing subconsultant to deglaze the windows on the ground floor and upper floor to get a sense of sill conditions. The upper floor, which is shown here, were in worse condition just simply due to exposure. During construction, we also found more corrosion of the first floor sills, which were partially covered by the granite flavors, and as you can see here, we have metal loss.

So why is corrosion of the steel so important? The original curtain wall glazing support was comprised of simple steel shapes and the glazing pocket was formed by steel bar stop secured with a quarter-inch flathead metal screw. The three-eighths inch plate glass is set into the pocket onto neoprene setting blocks in a neoprene shim separating the glass from direct metal contact. The assembly is made weathertight through the use of butyl tape of the exterior.

The original details for the ground floor is shown here, which shows the sill I just showed on the previous photo comprised of two C-channels welded together. So any loss of the metal due to corrosion would impact the structural support of the glass. Understanding deterioration mechanisms and existing glass behavior and performance was critical for this project. Martina will now discuss the owner project requirements or OPR and the many replacement options and design considerations that went into this project.

MARTINA DRISCOL

Still shocking to see those corrosion pictures, I swear. As with most projects, we started with understanding what the owner wanted. What was the OPR? This included a review of the library design guidelines that were authored in conjunction with the D.C. Historic Preservation Office. We talked with various stakeholders and we've reviewed several samples with the library and discussions with them resulted in several requirements that were a bit surprising to us at first considering that it is a library.

They indicated that UV protection, acoustics and thermal improvement were all deemed desirable but weren't necessarily critical if it really affected the historic property. The library was in favor of bringing all glass into alignment with current safety glazing requirements, whether they were currently cracked or not. This would also improve impact resistance at grade where most of the vandalism occurred.

We also discussed the fact that the introduction of safety glazing would allow for the removal of these retrofitted horizontal safety bars that were added at some point after the original construction. DCPL also agreed that the first floor glass may be treated differently, I guess, more strictly than the higher three floors due to the higher public visibility there and the historic importance of transparency that Becky mentioned.

So the first question was can we save any of it? Can we save any of the original plate glass and maybe even use it on one facade? This option was pretty quickly dismissed as the original glass alone didn't meet the requirement of safety glazing and it was deemed impractical to remove ship and laminate the existing lights. So once that was figured out, a mixture of laminated and heat-treated options were considered including laminated glass with and without a neutral low E coating and an insulating glass unit.

Low iron glass as shown in the picture here, was selected for the first floor as that low iron content results in a higher light transmission and the green tint of traditional glasses is significantly reduced. Two glazing types were ultimately selected for full-scale trial installations on the ground floor, no surprise, I guess. But the low E coating was eliminated due to the impact on clarity and the fact that this glass is shaded by the building above, so less prone to solar heat gain and the IGU was eliminated due to the effect on the glazing pocket depth and the concern regarding potential distortion of the fully tempered glass.

Similar to the first floor, four options were considered for the upper floors and three options were installed as full-scale mock-ups. DCPL did agree to consider an IGU and low E coatings at these levels. You can see the distortion in the heat strength and laminate and the pillowing in the insulated glass unit in this photo.

Per Mark's comments, they did decide on an annealed laminated glass for both the lower and upper floors. Despite the lower thermal performance and lower strength versus the heat treated options, they decided that the presence of the low E coating on the upper bronze lights was okay. They thought that was visibly visually acceptable, so they were able to decrease solar heat gain at the majority of the building glazing.

Once these went into production, I'll just note you can see the 5/16th in bold here. The glass thickness was increased from a quarter inch to five sixteenths as the manufacturer said, that was the minimum thickness they felt comfortable handling at the glass sizes, which were about nine feet by 10 feet. So nothing to do with performance per se, but rather with constructability. And as part of the decision making process, we also did take a look at those thermal stresses that Mark mentioned.

Real quick here. The industry standard for specifying glass in the United States is a probability of breakage at the first experience of the design wind load of eight lights in a thousand or less for vertical glazing and one in a thousand for glazing slope more than 15 degrees for vertical. It's also a commonly used probability of breakage limitation for thermal stress. So we did run that analysis as Mark described, and the original bronze plate glass. So we wanted to see where we were starting from. It did result in a high theoretical probability of 0.77.

Now again, Mark said, conservative. We acknowledge that that risk didn't appear to align with the reported number of breaks occurring IRL in real life. So the selected laminate reduced that theoretical probability by roughly 75% and polishing the annealed glass edges, which is typically assumed to increase the strength of the glass by 20%. It brought it back further down to 0.056.

So though that doesn't meet the industry standard probability based on the fact that cracking in the glass would not result in the glass falling from the opening thanks to the laminate and the fact that most past breakage was attributed to corrosion of the glazing pocket or vandalism, we were comfortable with that breakage probability trade-off. And just a quick note that no breakage has occurred since it was installed in 2020 and would expect to see that breakage by now if thermal stress was going to be a concern.

As Becky discussed, glass isn't used alone. So how did those final selections affect the iconic museum steel frame? The original glazing pocket dimension of five eighths inch was increased by 5/16th for the bigger glass and increased again by one-eighth to provide a more durable exterior silicone seal.

We ramped that seal slightly to promote drainage and ramp the interior seal to try to minimize the visible impact of that exterior ramp. The decision was made to retain the original stops or replace them in kind rather than decreasing them in size to match the original offset. This did result in a chamfer at the inside corners of the stops. At the upper floors, we similarly offset the interior stop, but had to hold it off with a new metal bar shim.

As the exterior seals at the upper floors would be harder to maintain and maybe less visible. We decided to gap this bar shim at the sills to allow for any water that might gain access into the pocket in the future to drain out. Now it would drain to the interior, but we figured this would alert maintenance staff to a concern and limit the risk for frame corrosion. So we're now going to shift gears a bit. While this next project doesn't include large floor-to-ceiling glass lights like the previous study, it is still a modernist building with glass issues and it's a study in replacement and preservation.

BRYAN ROUSE

This is the United States Air Force Academy Cadet Chapel in Colorado Springs, designed by Walter Nash of SOM Chicago in the late 1950s. It along with the rest of the cadet area was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2004, and it holds the title of the most visited man-made structure in all of Colorado. One of its striking features is the vertical ribbons of colored glass stretching from the floor to the ridge of the vaulted space.

These strip windows, as they're known, create an amazing light effect in the Protestant Chapel and we're not even seeing them in their full glory. That's because as for beautiful as this building is, it suffered from water leakage since before it was officially opened. And early on it was concluded that the strip windows were a source of some of that water. So while still under construction, exterior storms were added storm windows that were never part of the building's original design.

On the right, we can see what was planned, the strip windows fully exposed to the exterior and on the left storm windows being installed. Unfortunately it gets worse. In the 1970s, a new generation of storm window is introduced. This one sat 12 inches away from the original glass. Its openings were narrow. Nothing about them really aligned with anything from the original layout. And the wired glass, safety glass of the era completely obscured what lay behind.

It also left portions of the glass completely devoid of daylight. To see why storm windows were added, it's helpful to understand how the windows were built. Each ribbon of strip window is actually a series of individual units or cassettes stacked one atop another, similar to a modern unitized curtain wall. And each cassette consists of 9 to 12 colored dalle de verre glass blocks set in an aluminum frame.

There are 64 strip windows each holding 35 cassettes. That's 2,240 cassettes, and they hold 24,384 individual glass blocks. And according to the project records, approximately one-third or 8,500 of those glass blocks were hand distressed with a hammer, a scene in the middle photo to refract light. With the perimeters of each individual block and each individual cassette representing potential leak points, we can start to understand how shielding them from water became the name of the game.

But despite the added storm windows and numerous other repair efforts on the exterior skin of the building, water leaks persisted. So in 2014, having grown tired of failed attempts to repair what was already there, the government engaged AECOM and their team, which includes WJE as the exterior enclosure specialist and Hartman-Cox as the historic preservation consultant to develop a re-cladding design. While the overall re-cladding project reaches far beyond the strip windows and is a webinar in and of itself, today's focus is the vertical ribbons of colored glass.

The dalle de verre glass is clearly a defining feature of the building and saving it was a given from the start. That's our preservation part. But those unsympathetic storm windows that hide the true design of the strip windows, those have to go, and that's our replacement part, but the cassettes can't really be preserved and made watertight. So to create a watertight building, we'll continue to use a storm window approach, but one that maintains as much of the original design intent as possible while providing a functional window system, one that preserves and reveals the historic dalle de verre cassettes.

The solution incorporates a new line of glass nestled into the profile of the original enclosure scheme. We will see how we did that in just a bit, but first, let's look at the efforts to preserve and restore the dalle de verre glass and their cassette frames. As part of the project, all 2200 cassettes are being removed. Each one fully documented and cataloged as it comes out to ensure it goes back in the exact same spot later.

They're then created and shipped to Judson Studios in Los Angeles, California, the same place they were originally fabricated nearly 65 years ago. There the restoration work begins. After spending decades concealed behind storm windows, the cassettes were covered with dirt that was never washed away by the rain, and in some cases, the individual pieces of glass were virtually buried in ceiling.

So upon arrival, Judson Studios, each cassette is cleaned and each piece of dalle de verre glass is assessed for damage. To preserve the historic fabric, 300 cracked dolls were removed and epoxied back together before being reset into their original aluminum cassette. But one piece, one of the 24,384 dalle de verre glass blocks was simply too damaged to be put back together. It had multiple fractures and missing glass. So in this one instance, the block needed to be replaced, but doing so and replicating the color from 65 years ago posed a significant challenge, a challenge with a unique solution.

The glass block would be recast by melting down the original piece. Making that happen meant 3D scanning the original block. From there, a replica was 3D printed so that rubber mold could be made. The rubber mold was then used to cast a wax copy of the original dalle de verre piece. The wax replica became the source for creating a plaster mold for casting the molten glass. After cooling or annealing for four days, the recast doll was hand distressed by hammer in the same places as the original matched through graphite rubbings taken of the original doll before it was melted down. The replica dalle de verre glass block formed from historic material was then reset within the cassette.

With the preservation of the dalle de verre cassettes complete, we turn our attention back to how we're going to place these back into the building, shielding them from the water they can't manage on their own, and yet still allowing them to be seen both inside and out in their originally intended glory. Now, the 1970s storm window used wired glass, glass that completely obscured the view of the strip windows from the exterior. To increase the visibility, our replacement glass is a monolithic sheet of laminated glass and it uses clear low iron glass to remove the green tint associated with modern glass manufacturing methods mentioned earlier today.

Now we need a place to put the glass, a place that won't reduce the daylight opening and a place that will respect as much of the original design intent as possible. For that, we turn to the original building design where we can see that the cassettes were set into a glazing pocket and secured with an exterior glazing stop. To preserve the interior appearance, we need to keep the cassettes in the same place to preserve the exterior appearance. We also want to maintain the edge of the exterior cladding. That leaves us just under two inches to work with.

So our new piece of laminated glass is glazed into an aluminum frame that sits outboard of the preserved dalle de verre cassettes, occupying the space previously taken up with the cassette glazing stop. And while we refer to this as a storm window, it is in reality the window itself. With our new laminated glass and its frame fully incorporated into the air and water barrier of the overall building enclosure, the building remains dry without the cassettes present. As they were unable to manage water on their own, they become window treatment meant to preserve the historic design and allow the flood of colored light throughout the space.

Since the project's currently under construction, I thought I'd leave you with some images of the contractor's aesthetic mock-up complete with the intended appearance of the dalle de verres, thanks to a little help from Photoshop. So why is all this important? Well, many buildings built during the modernist movement are reaching an age when significant restoration and repairs is likely approaching. Understanding the benefits and challenges associated with glass selection is critical to addressing these buildings appropriately.

You want to keep in mind that decisions may rely on both analysis and engineering judgment to assess risk in the context of historic preservation, and sometimes replacement or preservation may be the right choice for the building. There are also several other aspects of glass and glazing advancement that may be appropriate for glass replacement projects, as well as a myriad ways to reduce the negative aspects of contemporary glass that we didn't have time to discuss today.

Some of the terminology and links to additional resources can be found in the reference handout provided with today's webinar. That document can be found in the resources list on the right-hand side of your screen. On behalf of Becky, Martina, Mark and myself, thank you for allowing us to share with you today. And with that, I'll turn it back over to Liz for questions.

LIZ PIMPER

All right, thanks Bryan. And thanks Becky, Martina and Mark for the great presentation. All right, our first question is are there any special considerations when cleaning modernist glass?

MARK SCHMIDT

This is Mark. I would say I generally try to closely follow the technical paper put out jointly by the National Glass Association and the International Window Cleaners Association. And I'd say it's carefully crafted because they each have opposing interests in maintaining the glass and not scratching it. And so while I wouldn't say there's anything special about cleaning historic glass, I would definitely lean toward that document for guidance.

LIZ PIMPER

All right, our next question, what information do you have for repair or replacement of exterior glass block at a front entry?

BECKY WONG

All right, so glass block is pretty unique and we didn't cover it in today's webinar. I think the patterns in particular for historic glass block is very difficult to replicate with off-the-shelf solution. There are some limited manufacturers who may, depending on the size of how many blocks you need, be able to help with replication. Otherwise, I've had to get back to salvaged pieces. But if you want, maybe we can connect to the side and I can provide you with some additional insight if that is okay.

LIZ PIMPER

I'm sure it does, Becky, sounds like a good plan. All right, our next question. How is roller wave distortion measured? Is there an industry standard for how much roller wave distortion is acceptable?

MARTINA DRISCOL

I'll give that one a shot. This is Martina. I don't believe still, there's no ASTM standard. For example, for roller wave distortion 0.003 inches peak to valley is a commonly used internal standard by several fabricators. So it's the actual glass fabricators that are identifying what their limitations are. It can be measured in terms of curvature as well rather than absolute dimension. A couple of manufacturers like Viracon and Vitro, they give these milli-diopter standards.

But in our experience, mockups are the best way to establish those expectations with respect to roller wave, and this is true with a couple of these issues. There are what they call online measuring systems that help to identify at least when glass may fall outside of certain guidelines. That's also true for an isotropy. They've definitely figured that out for that with a single pane. And they're getting there, I think with insulating glass units. So as I mentioned, when you put them two together, they can actually amplify the issue as is true with roller wave if you laminate two pieces of tempered glass, for example.

LIZ PIMPER

Yeah, that's a good lead into her next question, Martina. Someone asked Mark, did you have something to add there? Sorry.

MARK SCHMIDT

Yeah, I just had something to add. While there's no ASTM standard that governs the limits for either the peak to valley or diopter measurements you were talking about there are test standards and those are ASTMC 1651 and C1652. So those would be test standards. They don't include the limits that Martina just described.

LIZ PIMPER

So there's another question here, Martina, about vacuum insulated glass and whether it was considered for the MLK Jr. Memorial Library?

MARTINA DRISCOL

Yeah, that's a great question. We actually include a link to one of our other webinars on vacuum insulated glazing in our reference list. We didn't consider it for MLK. It does have the benefit of being thin, but it is really, it hasn't gotten there with optical clarity yet. You still have little standoffs that are required to keep the two pans of glass apart. There is a fledgling ASTM group on VIGs though, if you're interested.

LIZ PIMPER

All right. Our next question, have there been any developments in making older windows that are glazed from the interior side that could have the glass replaced from the exterior side? I asked because my institution has built walls and put objects on those walls that cannot be easily removed.

MARK SCHMIDT

I can take that. There are some systems like the Bruce System that was made to be reversed in terms of interior to exterior glazing, but it sounds like you may have a system that doesn't accommodate that readily. And if there's room, you would probably only need to cut the head of the opening to remove and replace the glass and then mend the head back and potentially covered it with an overlay. So it's quite doable. And depending on the visibility, you might not be able to tell that any repairs were performed.

LIZ PIMPER

All right. A couple of questions coming in or comments that folks can't see the reference list or some of the documents that we're referring to. A couple of them were added during the webinar today. And so when you refresh your screen at the end of the webinar, those will appear. Also as a heads up, we'll send an email to all attendees this afternoon with a link to re-access the webinar console. So if you don't see those reference items right now, you'll have access to them later today. Okay. This is a question from Martina about the MLK library project. Did the District of Columbia provide any guidance on thermal performance?

MARTINA DRISCOL

They really didn't. They didn't put a limitation on it. In fact, we were a little surprised by that. We thought for sure that they would need that. We did do a study in advance. I think there was a question on pre-design work on MLK. We did do a study on condensation and surprisingly found none. We monitored it over a season and it performed okay. Part of that is the bronze coloring to the glass, but their definite focus was maintaining the Miesian character of the building.

Now, we did go back and forth a little bit because Mies was part of his fundamental philosophy was using the technology of our age. So we used that to get us comfortable with going to even go into the laminates with a low E on them. But what the library ended up doing was just dealing with some of that energy with the mechanical systems. So not particularly green, but in line with, I guess, the aesthetics of the Miesian building.

LIZ PIMPER

Becky, do you have anything to add there?

BECKY WONG

Yeah, I think part of it, because we received a few questions about how we did the project, is we also had a design build approach. They were able to work with some mechanical engineer on what she would like to see in the building. And then what was interesting with Martina and I going through the OPR is they're more concerned with the aesthetic impacts of the historic building than protecting books from UV exposure and having a high building. So it was really interesting.

And when we did our thermal analysis, there were a few curve balls we had to take into account. You have a high heat mass with the black steel curtain wall, you have dark bronze glazing, and then they did want to add blinds because there needs to be some kind of comfort for the occupants. So all of that went into the analysis, and like they said, the probability of breakage was super conservative and we improved what was there originally.

And then through our mock-ups, because we had such a great design process, we did a lot of pre-design work for the study. So the library knew what the condition of the building was and their programming options. And then through the design build process, we had a lot of trial repairs, which helped us through the glazing selection and consultation because we had D.C. SHPO, which is the State Historic Preservation Officer and the Commission of Fine Arts to consult with.

And they were amazing to work through the process. They understood the intent, the need, and even the slight increase in the glazing, which I saw was another comment, which we tried to minimize. But with contemporary glass fabrication and having to ship overseas, there has to be that safety component too. So yeah, it was a really interesting process to get to that design and be part of a team.

MARTINA DRISCOL

Becky, I'd say we did some significant pre-design work on the coating.

BECKY WONG

Yeah.

MARTINA DRISCOL

More than the

BECKY WONG

Yeah, that's a whole presentation.

MARTINA DRISCOL

Yeah, that's a presentation.

BECKY WONG

Yeah.

LIZ PIMPER

All right. Our next question, at what point would you consider replacing with acrylic or polycarbonates? Can you discuss the ASTM or other standards that one should take into account when putting glass or plastic in an exterior environment?

BECKY WONG

Yeah, I can briefly say that acrylic and polycarbonate would not withstand the test of time with UV exposure, even through thermal cycling and winters. I would not consider it personally. I would see if there's other opportunities for you to utilize glass.

MARTINA DRISCOL

I think for MLK in particular, Becky, I think you mentioned it. They are getting more stable, right? They're not the old vinyl window, but they're very bulky, right? You don't get the thin steel effect with those windows.

LIZ PIMPER

Bryan, this is a question for you about the Air Force Chapel. Was there any water penetration in the field glass curtain?

BRIAN ROUSE

Yes. So as I mentioned, the chapel's undergoing a very expansive project. The reality is that the aluminum cladding and all of the glazing is coming off, the building's being taken down essentially to its structural steel frame of tetrahedrons and then being reconstructed. So the other portions of glazing on the building are also being worked on.

LIZ PIMPER

All right, probably got time for one more question. It's a good one. So do you see tempered or laminated glass often those seem like the best of both worlds, or are there downsides to this?

BECKY WONG

In historic buildings, do you always take into account what was the original glass fabrication? As a preservationist, sometimes you have to consider stability code requirements and safety, and I think we provided some really good options for you to keep that flat low to no distortion option with annealed glass to still be considered safety glazing, even in really large format.

Sometimes you just can't avoid it and you need to incorporate the heat treated or tempered glass. But when you get into that, it's also understanding can you adjust your specifications to minimize some of that distortion. You'll never be able to get rid of it until there's some advancements. But Martina, Mark, did you want to weigh in at all from your perspectives?

MARK SCHMIDT

I think Martina mentioned as well that if you laminate two pieces of heat treated glass together like tempered or heat strengthened, there can be greater distortion than just monolithic sheet of tempered or heat strengthened glass. Particularly if those say there is a little bit of roller wave in the glass and they're not nested, then they can amplify each other and create even worse distortion and more so in transmission than in reflection. So it's not really the best of both worlds from an aesthetic point of view, but certainly it has its place tempered laminated glass for say glass balusters or something like that.

LIZ PIMPER

Okay, great. Well, unfortunately that is all the time that we have for questions today. There's a lot of good questions that have come into the inbox, and as I mentioned before, they will not go unanswered. One of the presenters will follow up with you after today's webinar. Thank you all for joining us. We hope it's been educational. And thank you again to all of our presenters for the great information that they share today. Again, thank you so much for your time and we hope you have a great rest of the day.